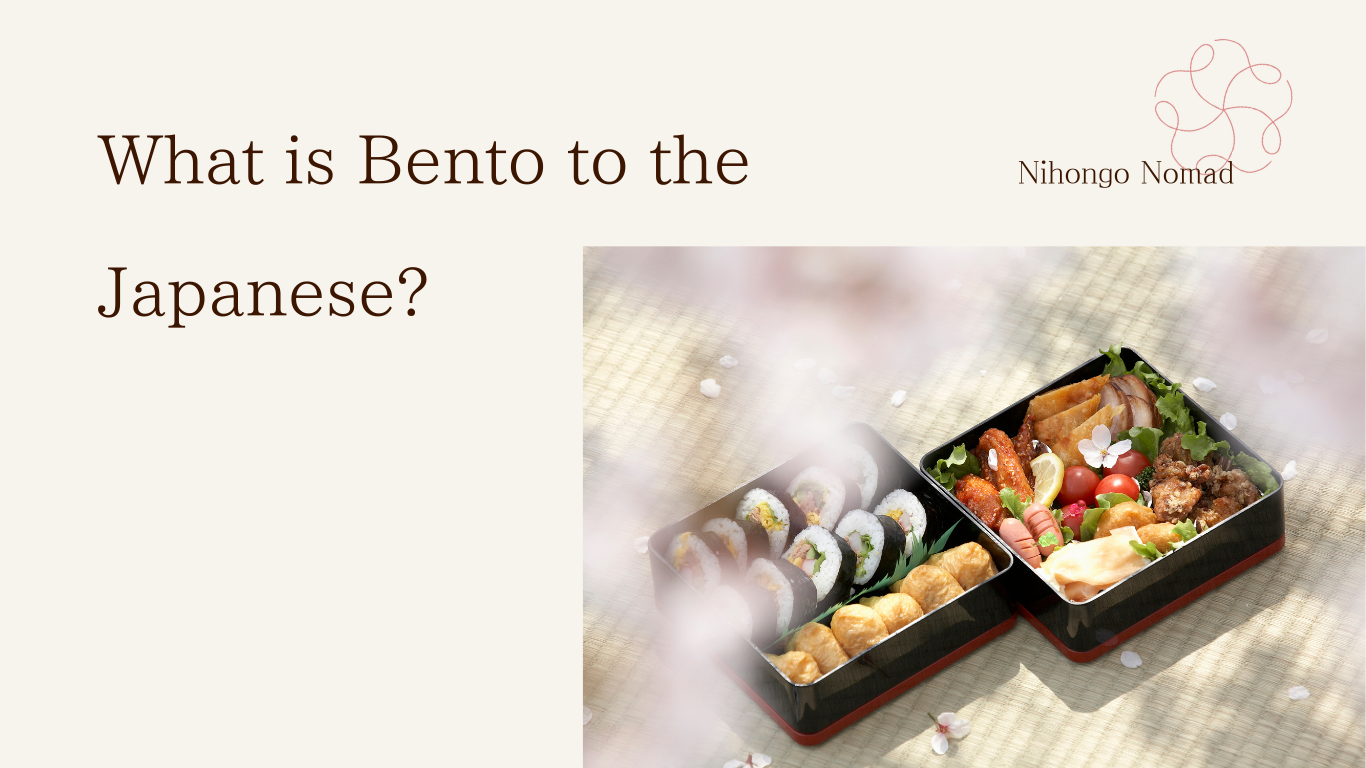

What is Bento to the Japanese?

To many Japanese people, a bento is more than just a packed lunch. It is a cultural tradition, a form of entertainment, and an expression of care. Whether it’s a lunchbox for school or work, a beautifully arranged ekiben eaten on a Shinkansen, a hanami bento enjoyed under cherry blossoms, or a character bento (kyaraben) shaped like anime figures—bento reflects Japanese aesthetics and values. Recently, bento culture has gained attention worldwide, especially in France and the U.S., where “BENTO” has become a trend.

Bento Goes Global

Books about Japanese bento are published abroad, and the word “bento” is now included in foreign dictionaries. The global bento boom began in France, where interest in Japanese culture is high. Manga and anime have also played a key role—many readers first encountered bento in scenes where characters share lunches, prepare them with love, or express emotions through food.

Origins of the Word “Bento”

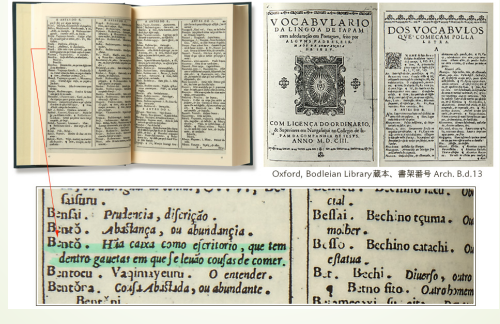

The word “bento” is said to originate from the Chinese word 便當 (biàndāng), meaning “convenient.” It entered Japan during the Southern Song dynasty and was adapted to mean “something prepared and carried for use.” It appeared in historical dictionaries such as the 1603 Nippo Jisho compiled by Jesuit missionaries.

Historical Timeline of Bento

The Origins of Bento: Ancient Portable Meals in Japan

From 1400 BCE to 3 CE (Jomon to Early Nara Period)

When we think of bento today, we imagine a beautifully packed box filled with rice, vegetables, and meat, ready to be enjoyed at school, work, or on a train ride.

But did you know that the roots of Japan’s portable meals go back over 2,000 years?

No Lunch? No Problem—Two Meals a Day

Until around the 1600s, it was common in Japan to eat just two meals a day—morning and evening. There was no standard lunch as we know it today, so the idea of a mid-day bento didn’t really exist.

However, historical records like the Engishiki (a Heian-era government manual compiled in 927 CE) mention that during physically demanding rituals or labor, people were allowed to eat a small rice meal as a snack—what we might consider an early form of bento.

Rice Balls: A 2,000-Year-Old Tradition

One of the most iconic items in a modern bento, the onigiri (rice ball), has a surprisingly ancient history. Archaeological excavations from the Yayoi period (over 2,000 years ago) have uncovered carbonized triangular rice shapes, suggesting that early forms of rice balls were already being made and carried for meals outside the home.

The Beginning of Portable Food

So, what did people eat when they had to leave home for hunting, farming, or ceremonies?

They relied on “keikou-shoku”, or portable meals—foods that could be dried, preserved, and easily carried. These early packed foods were practical, simple, and designed to withstand long hours or travel.

Jomon to Nara Period (1400 BCE–3 CE): Early forms of portable food, like dried rice (hoshi).

Heian Period (794–1185): Bento mentioned in records like the Engishiki; rice used for snacking during rituals.

Kamakura Period (1185–1333): Officials ate onigiri-type rice balls called tonjiki.

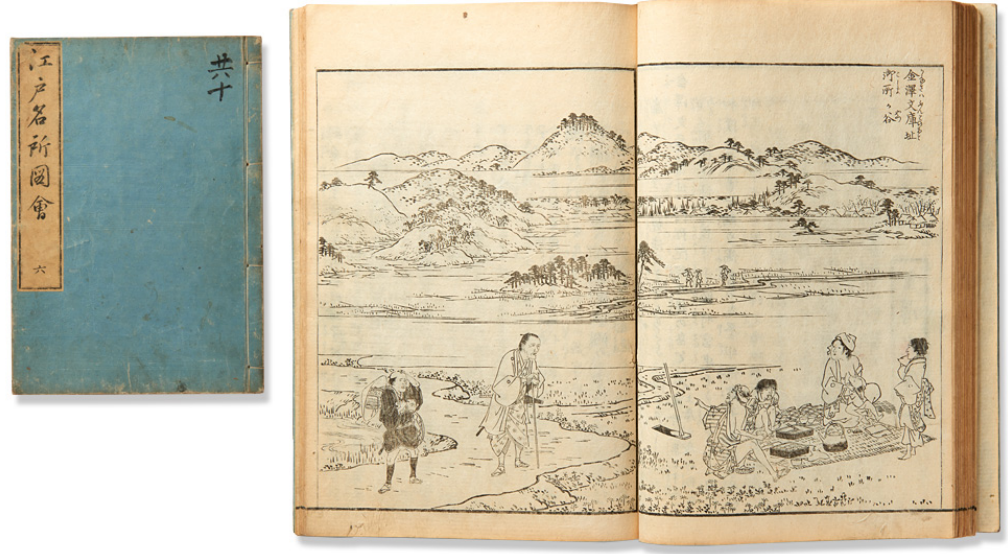

Edo Period (1600–1868): The three-meal system began; bento spread among common people. Farmers carried multi-tiered lunchboxes to the fields.

A Japanese–Portuguese dictionary -The Nippo Jisho compiled by Jesuit missionaries contains approximately 32,000 entries and offers valuable insight into historical Japanese vocabulary.

In this dictionary, the word “bento” (listed as bentau, 便当, 弁当) is defined as:

“A type of box similar to a stationery case, with drawers, used to carry food.”

This entry reflects how bento was understood and described during that time, providing an early glimpse into the cultural practice of carrying boxed meals in Japan.

The Bloom of Bento Culture in the 1800s: From Daily Meals to Elegant Outings

As Japan entered the 1800s (late Edo period), bento culture evolved dramatically. Thanks to the development of cookbooks and the rise of professional restaurants, food variety expanded. Bento meals, once simple and utilitarian, became increasingly colorful, seasonal, and creative.

At the same time, people began going out more often—not just for work, but also for leisure: cherry blossom viewing, boat rides, shrine and temple visits, and other cultural outings. This shift helped transform bento into a more refined and essential part of daily life.

The Gotōjō Bento: A Glimpse into a Daimyō’s Lunch

One of the most fascinating examples of 19th-century bento is the Gotōjō Bento—literally, “castle visit bento.”

This particular bento comes from a detailed food record kept in 1866 by Nobuoki Ambe, the feudal lord of the Okabe domain in Musashi Province.

On the day he was to report to Edo Castle (a formal duty of daimyō during the Tokugawa shogunate), his lunchbox included:

- Shiitake mushrooms

- Dried gourd strips (kanpyō)

- Miso-pickled daikon

- Onigiri (rice balls)

This humble yet balanced meal reflects both seasonal ingredients and careful planning—ideal for a busy day of political duties.

Interestingly, the contents of a bento would vary depending on the occasion. When Lord Ambe visited places like Zōjō-ji Temple or his secondary Edo residence (shimo-yashiki), the bento was considered part of a special outing, and the ingredients became a little more luxurious.

This era marked a major shift: bento was no longer just fuel—it became a thoughtful, elegant, and cultural expression, tailored to both purpose and place. Whether attending a formal obligation or enjoying a leisurely day out, people took pride in the care and creativity of what they packed.

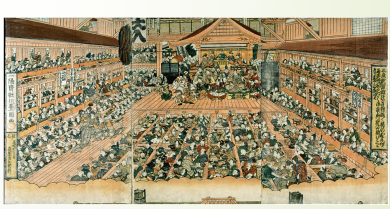

Theater and Bento: A Day at the Kabuki in Edo Japan

In the Edo period, going to the theater wasn’t just a quick evening outing—it was an all-day affair.

Kabuki performances often began as early as 6 a.m. and ran until around 5 p.m., making it a full day of entertainment.

Naturally, eating during intermissions became part of the fun. Wealthier patrons sitting in private box seats (sajiki-seki) would leave their meal arrangements to theater teahouses, which delivered food directly to their seats.

But for the general public, the go-to meal was the now-famous Makunouchi Bento—a boxed lunch enjoyed “between the curtains”, or in other words, between acts.

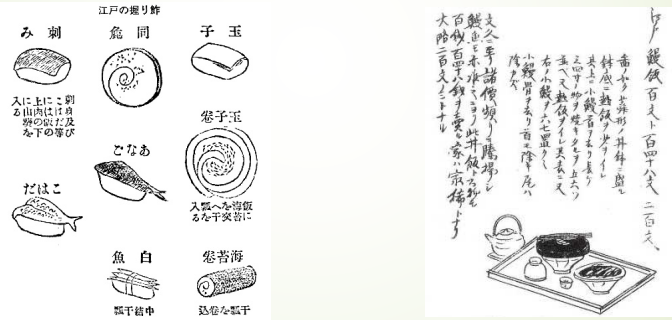

What Was in an Edo-Era Makunouchi Bento?

The term “Makunouchi” literally means “between the curtains,” referring to breaks in the performance when audience members would eat.

One of the earliest written descriptions of this bento appears in the Morisada Manko, a 19th-century encyclopedia of Edo-era customs and daily life.

Based on that text, a recreated Makunouchi Bento from the Edo period would typically include:

- Ten small rice balls (onigiri) Konnyaku (yam jelly) Grilled tofuDried gourd strips (kanpyō) Taro rootFish cake (kamaboko)Tamagoyaki (Japanese rolled omelet)

This well-balanced combination was simple, nourishing, and perfect for enjoying during a long day at the theater.

Meiji to Showa Period (1868–1989)

Bento diversified with new ingredients and became part of leisure activities like picnics and temple visits.

Modern Era (2000s–Today)

Bento evolved with lifestyle changes—convenience store bento, character bento, and global interest in BENTO as Japanese soft power.

Types of Bento

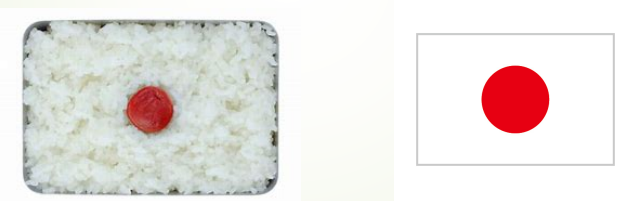

Hinomaru Bento:

Plain rice with a pickled plum in the center, symbolizing the Japanese flag. Popular during wartime.

Makunouchi Bento

Originated from theater culture in the Edo period; includes rice, fish, vegetables, and side dishes.

In Japanese theater terminology,

“the curtain rises” (幕が上がる) means the play is beginning,

and “the curtain falls” (幕が降りる) means the play has ended.

The term “Makunouchi Bento” (literally “bento between the curtains”) comes from this context—it refers to a boxed meal traditionally eaten during intermissions of theater performances.

Originally, theatergoers would enjoy these meals between acts, making the bento a part of the cultural experience of watching a play.

Shokado Bento

Inspired by kaiseki cuisine, this modern-style bento uses a box with cross-shaped dividers to separate elegant dishes.

Ekiben

refers to a boxed meal sold at train stations or onboard trains, specially prepared for railway passengers.

The earliest known example of ekiben dates back to July 16, 1885, when rice balls were sold at Utsunomiya Station in Tochigi Prefecture.As for the classic boxed-style ekiben (with compartments), it is believed that the first was sold by Maneki Shokuhin at Himeji Station in 1890.

Homemade Bento for School and Work

In Japan, homemade bento are commonly prepared in the morning and brought to school or work. These bento boxes are typically kept at room temperature and eaten without refrigeration or reheating.

Unlike in some other countries, it’s not customary to store bento in the fridge or warm them up in a microwave.

To prevent food from spoiling—especially during the summer—people often add preservative ingredients like umeboshi (pickled plum) or lemon, and place cold packs on top of the bento box.

Because the food will be eaten cold, it’s common to season dishes a bit more strongly than usual, so that they remain flavorful even when no longer warm.

Charaben (Character Bento)

Bento decorated with anime characters or cute designs, popularized in the 1990s and 2000s via blogs and books.

Kouraku Bento (Picnic Bento)

Large bento boxes shared during outdoor events like cherry blossom viewing or sports day.

Commercial Bento & Modern Boxes

Japan has countless takeout bento shops, supermarkets, and convenience stores offering a wide variety. Even online orders are available.

Bento Box Types

Plastic: Lightweight, practical, and available in many styles.

Stainless Steel: Durable, odor-resistant, long-lasting.

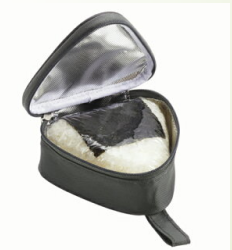

Insulated: Keeps meals warm or cold, perfect for extreme weather.

Wooden (Magewappa): Absorbs moisture to keep rice fluffy.

Aluminum: Lightweight, often with character designs.

Onigiri Cases: For transporting rice balls without crushing them.

Soup Jars: Vacuum-insulated for carrying hot soups or cold salads.

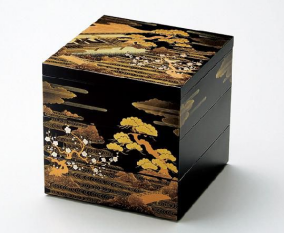

Jubako (Stacked Boxes): Used for special occasions like New Year’s, picnics, or unagi meals.

Conclusion

Japanese bento is more than just a lunch—it’s a story, a tradition, and an art form. Whether homemade or bought, it reflects love, creativity, and history in every bite. From rice balls to kyaraben, from lacquered jubako to plastic lunchboxes, bento continues to evolve and capture hearts around the world.

Next time you open a bento box, remember—you’re holding a little piece of Japanese culture.